Uyghur Separatism and the Politics of Islam in China's Western Frontier

Colin Cookman

From its earliest inception, the modern Islamic terrorist movement has been transnational and pan-Islamic in character. Osama bin Laden's Al Qaeda network had its origins in the corps of volunteers known as the "Islamic Internationale", or "Arab Afghans": young men hailing from Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and the whole breadth of the Middle East who flocked under the banner of jihad to the mountains of the Hindu Kush and the training camps of Peshawar. There they gathered to wage guerrilla war in the name of Islam against the godless Soviet Communists, while the American government looked on with grim satisfaction as it covertly supported efforts to bleed the Russians in their own "Soviet Vietnam".

Following the United States' campaign to topple the Taliban and disrupt Al Qaeda's base in Afghanistan in the aftermath of the September 11th attacks, news reports tracking captured fighters and key figures in the Al Qaeda leadership regularly reiterated, either explicitly or through non-commental labels of ethnicity, the multinational character of the terrorists' network: U.S. President George W. Bush's "coalition of the willing" was facing off against a stateless, loosely affiliated coalition of the dispossessed, the globally marginalized, and the violently revivalist. Although the biggest names and largest percentage of captured Al Qaeda members continue to be primarily of Middle Eastern or South Asian origin, every now and then reports mention other, more exotic figures in the mix of captured and killed: Chechens from the Caucuses, Uzbeks, Filipino Moros, and, infrequently but not unnoticed, Uyghurs from China's Xinjiang province.

What motivates those small handfuls of anonymous young men to cross the Pamir mountains into Afghanistan and fight alongside the militants of Al Qaeda and the Taliban? In order to attempt an answer, we must examine the origins of Xinjiang's oasis peoples, the Uyghurs, and their aspirations for nationhood; the nature of Chinese rule over them today, and its effects on those aspirations; and the extent to which militant Islamic revivalism may have infiltrated China's western hinterlands, and what implications that holds for the Uyghurs and their region. This paper argues that China's discriminatory policies have, more than any other factor, served to alienate the Uyghurs and increase the appeal of militant Islam, in effect making Beijing's worst fears a reality.

Historical Roots of Uyghur Separatism The origins of the Uyghur people (whose name is also alternatively transliterated in some sources as "Uighurs" or "Ouighurs”) may be traced back to the Uyghur khaghanate of the 700s, which broke away from the Turkic empire and settled across the Tian Shan mountains in the area of the modern-day cities of Urumchi and Tarpan (Millward and Perdue, 40). The modern usage of the "Uyghur" name refers more specifically to the settled Turkic peoples of the string of oasis cities that encircle the desert shores of the Tarim basin. Their Turkic Indo-European origins make the Uyghurs ethnically distinct from the Han who dominate the eastern heartland of the Middle Kingdom, a point of considerable tension given the degree to which being "Chinese" and being ethnically Han have historically been equated.

Prior to the first generic usage of the Uyghur name in 1934 by the Han warlord Sheng Shicai, "Uyghurs" maintained far more localistic self-identities, tied primarily to their oasis city of birth rather than any broader sense of "national" unity. The result is a layer of identities, to the point where Uyghurs today can identify their ethnicity in terms of no fewer than five separate components, with varying degrees of salience for specific individuals in particular circumstances. Thus, a "Uyghur" can be variously a Uyghur; a Muslim; a Turk who is part of a greater Turkic world and a speaker of a Turkic language; a resident of a specific oasis town, which has its own special local culture ... and a citizen of China, however unsought this status might be. For Uyghurs, as for all individuals, precisely which aspect of identity comes to the immediate fore, and when, depends on the issue at hand and the social context. (Fuller and Lipman 338)With this in mind, it is an irony that through their adoption of the Uyghur label (an act undertaken in imitation of their mentor Stalin's similar groupings in the Central Asian ethnic republics) the Chinese have effectively given the fractious oasis people of Xinjiang a common national identity to unify around. They have also offered policies to unify against: as Justin Rudelson and William Jankowiak note, "To a large extent, the modern identities of Xinjiang's peoples have developed in response to China's current ethnic policies. No matter how vigorously Uyghur intellectuals deny it, 'Uyghurness' is a political construct shaped mainly by Chinese policies" (314). Though the Uyghurs have a long history in Xinjiang to draw on in building their new identity, its modern incarnation has largely been defined out of opposition to Han rule.

The principle expression of that Uyghur identity has been desire on the part of many to create — or, more properly in their view, re-create — an independent "East Turkistan Republic" or "Uyghurstan" in the province of Xinjiang. Although Uyghur nationalists imbue the idea with a long historical pedigree, the two physical manifestations of that idea in history to date have both been comparatively recent and precariously short-lived.

The sparks that brought about the establishment of the first East Turkistan Republic date back to 1932, when efforts were made by local warlord Jin Shuren to reclaim authority over the lands of the Hami, whose khan had previously enjoyed feudal semi-autonomy under the Qing imperial dynasty's rule. Jin had achieved his position through the murder of the previous Qing administrator, Yang Zengxin, who had asserted control over the province as his own personal fiefdom after the empire's dissolution in 1911 (Millward and Tursun 73-4).

Jin's autocratic and badly mismanaged rule, which had imposed heavy taxes on the poor Uyghur farmers in order to subsidize Han development of the best lands, exacerbated tensions, and by 1933 rebellion had spread throughout the province (Millward and Tursun 75). It is worth noting here that "[t]he rebellion in early 1930s Xinjiang was not a bilateral conflict between Muslims and Chinese. Although communal and ethnic concerns were important factors, and certainly contributed to its bloody character, the reality of the rebellion was complex and multisided. ... Besides the Uyghurs and the Tungans [Muslim Chinese], forces arrayed against the Xinjiang provincial government included Kazaks, Kyrgyz, and other Chinese commanders and armies" (Millward and Tursun 75). In the midst of the fighting, Jin was deposed and succeeded by his equally dictatorial military commander, Sheng Shicai, who was backed by the neighboring Soviet Union (Millward and Tursun 76). With the capture of the city of Khotan in the southern Tarim basin, a group of merchants, capitalists, and intellectuals — all educated in the Turkish-influenced jadidist tradition, which emphasized the study of modern science, history, and economics for the purposes of strengthening their nationalist movement — proclaimed the foundation of the Eastern Turkistan Republic (ETR) (Millward and Tursun 77).

Later described in official Chinese documents as the product of "'fanatical Xinjiang separatists and extremist religious elements'", the proposed ETR constitution maintained a role for Islam and shari'ah law, but was primarily concerned with modernization and reform of government in Xinjiang. Far more effective now as a symbol for modern nationalists than it was in actual existence, the ETR was never able to expand beyond its corner of power in the southern region of Kashgar and Khotan. Appeals by Sheng and Stalin's concern for the stability of his own Central Asian republics brought in two brigades of Soviet troops with accompanying air support and chemical weaponry, and by 1934 the ETR leadership was broken, having either defected to the Soviets, Sheng, or the Kuomintang (KMT) Nationalist Party, or otherwise fled to refuge in India and Afghanistan (Millward and Tursun 79). The abortive Republic had met its end, and Xinjiang under Sheng operated primarily as a satellite of Stalin's Soviet Union.

Sheng's frequent shifts of loyalty failed to endear him to either his Soviet patrons or the KMT, and in 1944 he was finally removed and replaced by a new KMT governor, Wu Zhongxin. The Nationalists' rule was characterized by rapid inflation and broken ties with the Soviets, upon whom the province had depended for much of its development under Sheng. Official policy at the time refused to distinguish the existence of Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and other minorities, declaring them all to be Han in origin — a Qing-era legacy that does not hold up to anthropological scrutiny (Millward and Tursun 81-2). In little more than a month after Sheng's departure, rebellion had erupted in the northeastern Kazakh areas, the Ili valley (where Russian influence predominated), and again in southern Xinjiang. The city of Gulja was captured by rebels in November of 1944 and the formation of what was initially called the "Turkistan Islamic Government" was declared by Elihan Tore, an Islamic scholar (Millward and Tursun 82-3).

Given Tore's disappearance in 1946 and replacement by the secular, Soviet-trained Ahmet jan Qasimi, the extent to which Islam represented a defining ideology for the second ETR is disputable. The republic depended heavily on Soviet support to sustain its efforts against the KMT, although popular resentment of the Chinese amongst Xinjiang's inhabitants was real. Pressure by the USSR to establish some form of coalition government with the KMT brought about a tenuous peace in 1946. The ETR government in Ili maintained its own military forces in a kind of quasi-independence, but the KMT worked to politically intimidate Uyghurs in the southern areas under their control, manipulating local elections so as to limit the spread of meaningful independence (Millward and Tursun 83-84).

As James Millward and Nabijan Tursun note, prospects for the second ETR were limited. Its position surrounded on either side by the great powers of China and Russia "dictated the options of Turkic nationalists in Xinjiang on the eve of the Cold War: 'independence' under Soviet tutelage or 'autonomy' within China. In retrospect, we may say that neither... promised real self-determination, though at the time the prospects may have seemed brighter " (Millward and Tursun 84). Despite these constraints, the ETR enjoyed popular support, and was effective in improving the local education, taxation, medical, and agricultural systems in the areas under its purview.

The KMT retained control of the south until the advent of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Liberation of 1949, when KMT governor Zhang Zhidong's surrender left the ETR as the CCP's only rival for power in Xinjiang. Negotiations began hesitantly, and after a July 1949 meeting in Gulja with a representative from the new People's Republic of China (PRC), the ETR leadership was invited to Beijing for further consultation. The plane crashed en route on September 3rd, killing all the many prominent figures on board, but local PRC authorities refrained from announcing the news until the People's Liberation Army (PLA) had begun occupying northern Xinjiang and the lands of the ETR. With the ETR government in disarray after the loss of its top leadership, and with hardened PLA units now taking direct control over the Ili valley, the second East Turkistan Republic soon came to an end (Millward and Tursun 86).

Xinjiang Under the Chinese Communist Party The arrival of the CCP army to the Xinjiang frontier could have initially been seen as a promising development for the Uyghurs, at least compared to the KMT rule that preceded them. The promise of Liberation was coupled in statements by Mao about the need to end the practice of "Great Han chauvinism", which might have been taken as an optimistic sign. The Party planned for the training and education of cadres from local ethnic groups to take over administrative roles within the region, and sent a relatively small detachment of 10,000 Han Chinese to aid and educate their Uyghur comrades. The right to self-determination of minority communities — up to and including independence, should they so choose — had been a part of the early Party platform.

Like the neighboring Soviet Union, however, the victorious Chinese Communists under Mao's leadership would become determined to exert control over the remnants of empire that they had inherited, all their egalitarian rhetoric to the contrary (Tyler 138). Extensive energy and mineral reserves made Xinjiang a crucial strategic asset for the PRC – some estimates suggest that over three quarters of China's mineral wealth is concentrated in the province (Rudelson 35; Tyler 208). The CCP worked hard at redirecting road networks inward towards the city of Urumchi, later linked to China by rail in an effort to bind it closer to the heartland’s economy (Rudelson 35).

A new policy of "national regional autonomy" — that is, government by each of the major Chinese nationalities in their area of origin — had been proclaimed in 1947 in advance of the Revolution's completion, but with victory this interpretation changed: "Wang Enmao, the first Communist boss of Xinjiang, explained that self-determination was something you could aspire to while under the yoke of imperialism. In any other context, it was just separatism" (Tyler 139). Under the thoroughly Han-dominated Party's infallible direction, the "Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region" (inaugurated in 1955) was purposefully gerrymandered into districts that minimized the governing power of the minorities they were purportedly set aside for. In fact, ethnic Uyghur party secretaries and other cadres served primarily as a facade for continued rule by Han cadres, who shadowed them in nominally subordinate roles (Tyler 139-141). The CCP solidified its control over the province, introducing land reform policies and targeting the local elite power base through a succession of early campaigns against "pan-Turkism" and other sins against national unity, seeking to merge all nationalities into a single Chinese nation just as the KMT, the warlords, and the Qing had aimed to do before them (Tyler 145).

The ideology of "pan-Turkism" — the recreation of a band of Turkic states stretching across Central Asia from the homeland of Ankara to its terminus in Xinjiang — has been a long-standing motivator for Uyghurs, but in recent years this transnational vision has faded in favor of more local focus (Christoffersen). For all their short-lived nature, the two East Turkistan Republics loom large in the dreams of modern Uyghur nationalists, who hope to one day see the goal of independent self-government realized in full — a fact of which the current Chinese government is well aware. The very act of researching any of the pre-1949 history of the Uyghurs counts as a political crime in Xinjiang. Christian Tyler relates "unconfirmed reports from Kashgar [claiming] that in May 2002 more than 32,000 copies of a book with the innocent title Ancient Uyghur Craftsmanship were destroyed by the state-owned Kashgar Uyghur Press", together with copies of two other Uyghur histories (Tyler 159). Authors writing on such topics are accused of "endangering the unity of China" and may face imprisonment or worse; Uyghur exiles complain that only a sixth of all books published in Xinjiang are written in the Uyghur language — none of them Islamic texts, even the Quran — leaving them without a dictionary, contemporary encyclopedia, or modern literature with which to preserve their identities in the face of the Han cultural juggernaut (Tyler 158).

Although access to the internet is restricted within China and many neighboring Central Asian republics, where a large portion of the Uyghur expatriate community resides, over twenty-five prominent web sites, mostly maintained by Uyghurs who left Xinjiang prior to Communist Liberation, reach approximately half of the estimated one million Uyghurs living outside Xinjiang.

Most, like the International Taklamakan Human Rights Association (http://www.taklamakan.org), the East Turkistan Information Center (http://www.uygur.org), and the Uyghur American Association (http://www.uyghuramerican.org/) are focused on serving the international exile community and drawing external attention to the Uyghurs' plight, with predominantly English-language sites ("Cyber-Separatism and Uyghur Ethnic Nationalism in China" 16). About half are dedicated to open independence advocacy, while the others are focused more generally on providing information about the Uyghurs, their history, culture, and current political situation; a few of these latter sites are sometimes accessible within China itself depending on political conditions ("Cyber-Separatism and Uyghur Ethnic Nationalism in China" 9).

The Uyghur service of the United States' Radio Free Asia, the only government-sponsored news service dedicated to free dissemination of information about the Uyghur plight, is frequently blocked or jammed by the Chinese state, which views it as favoring the disruptive "splittists". Recently increased Sino-American cooperation in the war on terror has, in the view of some independence advocates, lead to a tempering of American criticism of Chinese government practices since 2002 ("Cyber-Separatism and Uyghur Ethnic Nationalism in China" 11-12).

Beijing does not limit its control over Xinjiang to the censorship of local histories. Beginning in 2001 the CCP leadership has implemented a concerted campaign of "Developing the West", a full-scale colonization program by mainland Han Chinese that has in the course of only a few years rendered the Uyghur a minority in the region that bears their name (a parallel program is being undertaken in Tibet as well). The statistics collected by Christian Tyler are stark: "In 1949, there were about 300,000 Han Chinese in Xinjiang in a population of 4 to 5 million, or about 1 in 15. For many years the number of Han was a 'state secret', for fear of provoking the Uyghurs. A census in 2000 showed 7.5 million Han in a population 19.25 million, or more than 1 in 3. According to the official figures, the Uyghurs were the largest group, with 8 million," but as is the case with much of China's notoriously suspect data, this number is misleading since it omits over three and a half million military servicemen, police, advisors, and the entire workforce of the state-owned Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps. Adding these, Tyler concludes, "the number of resident Han is nearer to 12 million, making them not only the largest ethnic group but close to becoming an absolute majority in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region" (Tyler 214). Although undercounting of Uyghurs may distort these figures further, a recent focus on enforcing previously lax birth control policies amongst ethnic minorities and rumored plans for a population target of 20 million Han by the year 2010 have many Uyghur nationalists labeling the "Great Leap West" policies as "demographic genocide" (Tyler 214).

Beijing's motivations for this immigration campaign are multifaceted, as it seeks to relieve population and employment pressures in the mainland; develop and exploit the mineral and energy resources of the remote western frontier in order to fuel the rapid expansion of the coastal Chinese economy; strengthen China's strategic position at its borders through a buildup of PLA military installations (until 1996 China maintained nuclear testing facilities in Lop Nor, inciting protests over fallout-induced illnesses in 1993); and cement political control over the restive Uyghur population through the process of deculturalization and economic and demographic marginalization within Xinjiang (Tyler 167, 208). The Great Leap West, Beijing believes, offers the possibility to accomplish all these goals simultaneously through Han colonization of Xinjiang. The aforementioned Production and Construction Corps (bingtuan) has been the primary organ tasked with its implementation within the province. The Corps is operated by the PLA as an entity parallel to the provincial government, and employs a seventh of Xinjiang's total population in a conglomeration of farms, factories, and associated production and transportation networks, while also operating the prison labor camps that function as China's own version of the Siberian Gulag. Although the bingtuan has faced reductions of its workforce and cutbacks as China makes a nationwide effort to dismantle its state-run industries, it remains dominant within Xinjiang not only as an employer but also as a provider of social welfare functions, all within one sprawling, self-contained work unit (danwei) (Tyler 194-5). The various branches of the Corps are staffed, directed, and populated almost exclusively by Han Chinese, who enjoy disproportionate access to employment and the benefits of Xinjiang's development.

Many Uyghurs remain marginalized within both the public and private sectors of the economy. Of the desirable "staff and worker" (zhigong) positions within the state and collective enterprises of Xinjiang (which account for almost 60% of all nonagricultural jobs) Han Chinese hold almost 70%, despite the fact that they comprise only slightly more than 40% of the total population of the province (Wiemer 180). While this can be partially explained by the concentration of Han within the urban areas where these jobs are most prevalent, Uyghurs regularly testify to discrimination on the basis of their ethnicity and religion. "The notion that 'minority nationalities' are inherently less intelligent, more backward, and less hardworking than Han, and that this is due in part to their practice of Islam, has great currency in China", with the result that finding work in the state sector becomes almost impossible for practicing Muslim Uyghurs (Fuller and Lipman 325). The official unemployment rate in 2000 for Xinjiang, while relying on PRC figures that must be considered suspect, was at 3.8%, as compared to 3.1% the state admits as the prevailing rate in the rest of the country; among Uyghurs that number has been estimated at 15% of the population or higher (Wiemer 180; Tyler 219).

Given the historical inclination towards commercial self-employment on the part of Han family business networks (as can be witnessed in the successes of the Chinese diaspora throughout a number of Southeast Asian nations), the prevalence of Han within the private sector economy may not be all that remarkable. As Calla Wiemer notes, however, "factors beyond the control of minority groups can also encourage or impede entry into self-employment ... minorities tend to be more intimidated by the process of securing licenses and approvals and to have greater difficulty obtaining financing" (180). Preferential treatment for Han Chinese corporations and workers when awarding contracts or jobs abounds throughout the Xinjiang economy; even fluency in Mandarin — a requirement for any gainful position in the province — and a university degree is no guarantee of employment for those in the Uyghur minority. Patronage networks favor Han Chinese for the best jobs, the best postings, and the most opportunities for promotion and advancement, and Uyghur employees are forced to stay silent to cling to what employment benefits they still enjoy, or risk an abrupt termination (Tyler 220-21).

Islam in Xinjiang under Chinese Communist Party Rule The threat against the Uyghurs is not solely a political or an economic one, however; those who rally the faithful against the spiritual oppression of the godless Communist Party will find no shortage of material with which to fill their sermons. Although the vigor with which the CCP has attempted to "de-Islamify" the region has waxed and waned with periods of "hard" and "soft" policy shifts designed to alternatively coerce and co-opt the Uyghurs, the CCP has made a generally consistent effort since taking power to control, suppress, and eliminate the practice of Islam within Xinjiang. Cultural assimilation of new generations of Uyghurs has been implemented both through force and other more subtle pressures. The process has particularly intensified in recent years under the aptly named "Strike Hard, Maximum Pressure" campaign, officially inaugurated in 1997 (Rudelson and Jankowiak 301).

This most recent government crackdown came in response to riots in Baren, a small town on the western edge of the province, where mass protests broke out in April of 1990. The closing of a mosque just days in advance of a religious festival led to clashes with security forces, and an unknown number were killed in the crackdown (tallies vary widely, from an official toll of 22 deaths to claims as high as 3,000 killed) (Tyler 165; Rudelson and Jankowiak 316). As Tyler relates it, the internal Party report on the incident described it as "'the most serious [riot] carried out by ethnic separatists since the Liberation of Xinjiang'. It had been planned well in advance ... by a 'small number of reactionaries and ethnic separatists hidden in Baren' ... The plan had been to set up, under the 'cloak of religion', an Eastern Turkistan Republic by armed revolt, and to eliminate non-believers (that is, the Han)" (165-6). Accounts from the incident spread throughout Xinjiang, and it was alleged that in the aftermath local security forces initially arrested every male between the ages of 13 and 60 in the town (Tyler 165). Similar uprisings in Ili, Gulja, and Kashgar, most of which originated out of disputes over the treatment of mosque-goers and religious scholars, were soon coupled with bombing campaigns in Xinjiang and within China proper.

A 2002 report by the Chinese State Council — entitled East Turkestan Terrorist Forces Cannot Get Away with Impunity — described more than 200 terrorist incidents since 1990, including bombings, assassinations, and even armed assaults on government institutions; the total dead was listed at 162, with 440 injuries (Christoffersen). These attacks have in turn been met with overwhelming force as the state sees itself under attack by "splittists" marching under the banner of Islamic jihad. The Chinese Communist Party, never friendly to the practice of religion, identified it as the cause of the rioting in Baren, Ili, and other cities; this was a self-serving interpretation in the view of Rudelson and Jankowiak, where, "instead of seeing Islam as a channel through which local Uyghurs are able to express social and political frustrations in a variety of areas, the government chooses to perceive it as the cause of those frustrations, which in turn gives rise to actions that further exacerbate the situation" (316).

Some of the Party's efforts to curb the influence of Islam almost resemble a satanic test of faith, as government employees, Muslim cadres, and schoolchildren throughout Xinjiang are offered free meals by the state throughout the day during the holy month of Ramadan in an effort to tempt them away from maintaining the fast (Fuller and Lipman 338). Similar offers of free alcohol have been made — and sometimes forced — upon Uyghurs, coercing them to violate of the Quranic taboo against its consumption (Tyler 157). In the raw upheaval of the Cultural Revolution, Party activists herded pigs into mosques in order to purposefully defile them (Kurlantzick 263).

Other current methods, if not quite as blatantly provocative, are equally intrusive upon religious practice, as state security organs conduct regular surveillance of mosque attendance and monitor the content of sermons and teachings. Uyghurs have been arrested for wearing headscarves or other forms of Islamic dress, employees of the state are forbidden from participating in daily prayer services, and, perhaps most daunting for the future of the faith, mosque attendance by those under eighteen years of age is forbidden (Fuller and Lipman 324, 341). The ability to participate in the hajj to Mecca, a central pillar of the Islamic faith, has been clamped down upon as well, with alleged border detentions of Uyghurs and restricted travel rights ("China Muslims face haj restrictions").

The result of this concerted assault been the weakening of the practice of Islam within the Uyghur community, as many imams are driven underground or out of Xinjiang entirely and the next generation of Uyghurs grows up unobservant or ignorant of the practices of their own religion. Suffering under the full brunt of the Chinese state's effort to overwhelm Islam, the future of the Uyghurs’ faith remains unclear, particularly when coupled with the demographic and economic challenges that the increased Han Chinese presence brings to Xinjiang society.

The Chinese state has implemented the practice of corporatism in matters of religious faith, as it has in more secular social organizations. Only registered clerics — now designated as "patriotic religious activists" — schooled at official state-run and -sponsored seminaries are permitted to practice their faith in public. The Institute for the Study of Islamic Texts in Urumchi is the only officially sanctioned madrassa in all of Xinjiang, and it remains subordinate to the national Islamic Association of China, headquartered in Beijing. Courses offered therein included "Marxism against Religion" and "The Works of Deng Xiaoping", and sermons on "the international solidarity of the working class"; the Marxist character of Islam is repeatedly emphasized as is the reactionary, backward, and superstitious character of all religious practices (Tyler 133, 158). Attending independent, covert religious classes outside the supervision of the CCP is grounds for arrest or worse; to do so is to be guilty of the crime of "illegal religious activities". By requiring that any imam serving in the region be a graduate of the Urumchi seminary, the government attempts to control and co-opt the Islamic leadership of Xinjiang, keeping it under strict surveillance and establishing the state as the ultimate arbitrator of their legitimacy as leaders of the faithful (Fuller and Lipman 333).

Horizontal associations of any kind are viewed as inherently threatening to the power of the Chinese state apparatus over society. "From the regime's point of view", according to Graham Fuller and Jonathan Lipman, "there can be no 'good Islam' in Xinjiang unless it is focused strictly on the narrowest details of religious practice. Least of all can it allow any searching inquiry into the place of a world religion in defining local community life and the values of its members" (341). That Islam, like the much circumscribed Catholic Church in central China, raises problems of dual loyalties within the population is cause enough for concern; the fact that it has formed a central component of Uyghur nationalist self-identity, and has served as a rallying point for Uyghur political organization and "splittism" makes it the embodiment of the leadership's worst fears and suspicions. The Impact of Militant Islam The extent of Islam's role as a defining influence within the Uyghur independence movement is heavily disputed by both sides. Evidence does exist to suggest that, contrary to the claims of the CCP, many Uyghur nationalists both inside and outside Xinjiang, despite strong personal religious faith, remain more focused on what is seen as an infringement upon their historical sovereignty (so claimed) and human rights, rather than religious appeals to jihad. For all Beijing's vocal protestations of the threat they face in Xinjiang,

China's Uyghur separatists are small in number, poorly equipped, loosely linked, and vastly outgunned by the People's Liberation Army and People's Police. Local support for separatist activities, particularly in Xinjiang and other border regions, is ambivalent and ambiguous at best ... Many local activists are not calling for complete separatism or independence, but generally express concerns over environmental degradation, antinuclear testing, religious freedom, overtaxation, and recently imposed limits on childbearing. ("Xinjiang: China's Future West Bank?" 269)

Dru Gladney's research amongst the Uyghur online community, described in part earlier, has found "almost no use of the term, let alone calls for a religious war against the Chinese" — not even what John Esposito terms "defensive jihad" to protect the faith from persecution ("Response to Chinese Rule" 391). Those who identify Islam as the principle source of danger in Xinjiang would do well to remember the existence of China's Hui minority, a group of Muslims ethnically indistinguishable from the Han living in the eastern Chinese heartland. Although religion is never an easy practice within the PRC, and the Hui suffer many of the same suspicions directed towards Uyghur imams and practitioners, by and large they have integrated with the rest of Chinese society and show little if any inclination towards violent separatism. Although tensions between Hui and Han do simmer — witnessed in a handful of quietly reported November 2004 news stories of Hui riots in central Henan province over land seizures — the general absence of any Hui interest for the Uyghurs' cause reinforces the contention that the conflict in Xinjiang is not so much a manifestation of the pan-Islamic call to jihad, but rather the product of local ethnic nationalism ("Several killed in ethnic clashes in central China: officials").

This said, the ability of militant Islamic revivalism to graft itself on to existing conflicts between Muslims and non-Muslim rulers has been demonstrated on several occasions within the past half-century, and the potential for a greater Islamicization of the Uyghur conflict is real. Underground Islamist groups in Xinjiang are believed to have received support for their covert educational and organizational efforts from sources including the Afghan Taliban, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), and the Jamaat-i Islami of Pakistan, whose curricula and political programs all emphasize a pan-Islamic, militant revival of Muslim rule (Fuller and Lipman 336). The IMU, which in June 2001 renamed itself the Islamic Party of Turkistan (Hezb-e-Islami Turkestan) has publicly dedicated itself to the creation of an Islamic state across the breadth of Central Asia, mingling pan-Turkic and pan-Islamic goals and expanding its recruitment activities throughout the region and into Xinjiang (Christoffersen). The doctrines of Ibn Taimiyah and Sayyid Qutb, which reject the illegitimate rule of infidels (kaffir) over the Muslim community of believers (ummah), offer a powerful rallying cry to the politically marginalized denizens of the Muslim world. The success of the anti-Soviet jihad and the independence movements of the Central Asian republics has offered further encouragement to Uyghur separatists (Yom).

Recent history has shown that the appeal of tapping into a global audience of wealthy supporters by emphasizing the Islamic character of a group's resistance has often proven irresistible. Fighters in places like Chechnya and Mindanao, where separatist movements had previously centered around ethnic and political conflicts, have now adopted a new pan-Islamic sheen that has opened up increased access to funding, materiel support, and insurgency training from sympathetic jihaddist groups seeking transnational influence. Fuller and Lipman, enumerating the range of recent historical conflicts between Islamic populations and non-Muslim rulers, note that In each of these cases, Islam powerfully reinforces the nationalist movement by investing essentially secular nationalism with religious overtones and emotional content of a more universal character. Yet, so far this phenomenon has scarcely been manifested on the Xinjiang scene. The key question is, Will it increase as we might predict? Or have the Chinese draconian policies made it nearly impossible for a widespread Islamist-based opposition movement to emerge? (340-1)

It has been noted by observers such as Ahmed Rashid and Robert Kaplan that in the cases of Afghanistan, Chechnya, the Central Asian republics and other violent hotspots for Islamic revivalism, the experience of growing up without any clear understanding of their own religious heritage (which had historically been more moderate, mystical and quietist in all three cases) often leaves a new generation of practitioners vulnerable to infiltration and co-optation by more virulent strains of religious fundamentalism emanating from salafist schools like the Saudi Wahhabi movement or the Deobandi Taliban. While the Chinese might be able to eliminate public practice of Islam through the powers of coercion and punishment available to them through control of the state apparatus, to the extent that memory of Islam's role as a defining part the Uyghur identity lives on in the consciousness of nationalists, there exists an opening for revivalists to establish a connection to that cause and exploit it.

It is this possibility — that the Uyghurs may turn towards foreign sources in the community of militant political Islam to feed their hunger for independence — that makes those news reports of captured bands of Uyghur mujahadeen in the caves of Afghanistan so alarming. In fact, when we examine the degree to which Chinese entry into the US-led "war on terror" has stymied their efforts to achieve some sort of redress in the international community for their grievances, it soon becomes apparent that as of today, Uyghurs possess few other outlets.

The Impact of September 11th Official Chinese government statements identify eight Uyghur terrorist organizations operating in Xinjiang: the Eastern Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM), the Eastern Turkistan Islamic Party, the Eastern Turkistan Islamic Party of Allah, the Islamic Reformist Party "Shock Brigade", the Islamic Holy Warriors, the Eastern Turkistan Islamic International Movement, the Eastern Turkistan Liberation Organization, and the Uyghur Liberation Organization (Rudelson and Jankowiak 317). Of these eight, the latter three are believed to be primarily secular in character. In January of 2001 Chinese authorities declared that the Eastern Turkistan Islamic Party of God had been destroyed, after a series of raids captured their leader, whose followers (eventually numbered at 113) had been blamed for a series of terror bombing throughout the province. The leader, Alerken Abula, was claimed to have had a "hit list" of mosque officials loyal to Beijing, and was sentenced to death upon his capture, which was believed to have been the effective end of that group ("Uyghur terror group smashed in raids"). Given the loose and fractious nature of the Uyghur political community, it is to be expected that new groups may emerge, outside those already listed here.

In the wake of 9/11, many prominent leaders of Uyghur nationalist organizations made an effort to publicly distance their movement from violent Islamism, holding a conference of the East Turkestan National Congress in Brussels of October 2001, and in their own words "strongly condemning the terrorist attack of 11 September on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon and terrorism and extremism in any forms" and expressing, "on behalf of the Uyghur communities around the world, its deepest condolences to the USA government, to the families of the victims" ("Resolution of the East Turkestan National Congress").

Little distinction is made by the Chinese government between these pan-Turkic nationalists and militant Islamists, however. Gaye Christoffersen suggests that

This is in part due to a widely distributed book published by the Xinjiang Academy of Social Sciences in 1994, Pan-Turkism and Pan-Islamism in Xinjiang, that reified and mingled both "isms" in Chinese thinking so that no distinction could be drawn between those Uyghurs who were Pan-Turkic in orientation and those who were Pan-Islamic — i.e., no distinction between those who trained in Turkey and those trained in Afghanistan; no distinction between those advocating Deobandism and those advocating modernity. Both were labeled as feudal and anti-modern. This reification of identity facilitates the military approach to terrorism, on which Beijing continues to rely in conjunction with the economic development approach. (Christoffersen)

Beijing has been especially interested to see its conflict with the Uyghurs placed under the legitimizing mantle of the war on terror, and linkages between Uyghur militants and Al Qaeda and Taliban forces have been highly publicized in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. This "bandwagoning" effort by Beijing has been particularly conspicuous given that, "In the past, Beijing had always publicly downplayed the level of violence in Xinjiang and tried to manage it discreetly through state-to-state negotiations with Turkey and Pakistan", suggesting that there is undoubtedly a degree of opportunism in many of the PRC's claims (Christoffersen). While this has led to some overestimations of the extent of contact between the groups, making numbers difficult to gauge accurately, best estimates indicate that as many as a hundred Uyghur fighters may have been aiding the Taliban at the time of the U.S. invasion, with another thousand militants in Xinjiang having passed through training camps in Afghanistan (Christoffersen).

Desperate to enlist more partners in its fight against transnational Islamic terrorism, the Bush State Department, in an August 2002 announcement by Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage, placed the EITM on the official U.S. list of terrorist organizations (Kurlantzick 265). The designation appears to have been made in haste and was motivated more by geopolitical concerns over Sino-U.S. relations rather than any evident threat the heretofore obscure group might have represented to U.S. interests. Despite the EITM's extremely peripheral role in Uyghur politics, Beijing now regularly refers to it — and its American designation — in all major speeches on the subject of terrorism. The result has been, in the estimation of Joshua Kurlantzick, a hardening of attitudes on the part of Uyghurs against the United States: "Xinjiang began to turn against Washington. Historically, [the Uyghurs] had been one of the most pro-American Muslim populations in the world ... but now [they] were becoming less pro-United States. Young Uyghurs increasingly decried Washington's policies in China, and began to associate the Uyghur cause with the struggle of other anti-American Muslim groups around the world" (266). Those Uyghur nationalists living in Xinjiang who have not given into despair altogether may be turning away from moderate leaders, after having suffered this latest blow to their cause from the Americans. The US has not been the only target of China's recruiting campaign: the neighboring republics of Central Asia, many of them still ruled by former Communist Party strongmen struggling with their own Islamist insurgencies, have also been receptive to Chinese persuasion. In 1999 the PRC established the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), a forum for the Central Asian nations, China, and Russia to focus on the threat to their interests posed by separatism, terrorism, and political Islam, all of which are regularly linked by Beijing. The PRC uses the SCO to leverage its power in the region and recruit support for its repression of the Uyghurs; the SCO also serves as a counterweight to U.S. influence in the region, seeking to assert that "Western interests should play no role in the internecine power struggles of Central Asia". (Kurlantzick 264; Yom). This comes to the detriment of Uyghurs (and other opposition movements) who seek to align themselves with the West.

Xinjiang has long been, in the words of Sean Roberts, "a land of borderlands", and the inhabitants of the ring of oasis cities surrounding the Taklimakan Desert have often looked first to their neighbors across the border before developing ties amongst each other or towards the ruling Chinese regime (216). While these strong cross-border links had previously proven useful for their economic potential as well as the degree to which they divided the population of Xinjiang and made Chinese rule easier, in the age of transnational terror they have proven a cause for concern. Contradictory cultural trends emanating from Afghanistan and Pakistan to the south and the former Soviet Central Asian republics to the northwest, bring, respectively, Islamic religious and political movements and more Western secular nationalist strains of thought into the Chinese frontier — both of which serve to threaten continued CCP rule (Roberts 225). Through organizations like the SCO, China has been successful in persuading these neighboring regimes to restrict the activities of the Uyghur diaspora living within their borders. As a result countries like Pakistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan have disbanded several Uyghur nationalist political parties and restricted their ability to congregate or put on events (Kurlantzick 265).

Reports by Amnesty International and the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights have raised concerns that China's neighbors are now increasingly willing to deport Uyghurs accused of terrorism by Beijing back to China, where they often disappear into the Chinese legal system, frequently facing torture and death (Kurlantzick 265). The military government of Pakistan, former sponsor of the Taliban and a major source of political Islamist ideological development and support, has come under considerable pressure by their Chinese ally to divest themselves of any Uyghurs, who have in the past been trained and supported by the Pakistani Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI) services (Christoffersen). Desiring to demonstrate its value to the Chinese as to the Americans, Pakistan has increased cooperation on this front in recent years, with handovers like that of Ismail Kadir, who was detained in 2002 in Kashmir and then repatriated after being identified by Chinese authorities as a leading militant separatist figure, and with raids on the ETIM and other militant Uyghur organizations operating within its territory. ("Separatist leader handed over to China"; "Musharraf: Bin Laden's Location Is Unknown"). Even Turkey, home to some of the most prominent Uyghur exile groups and traditionally a strong supporter of the rights of their ethnic kin in Xinjiang, has now banned formal Uyghur organization within their territory, though informal meetings among the exile community continue (Kurlantzick 265). China's clout as a rising economic power and a political force in Asia and abroad leave the Uyghurs hard-pressed to compete for friendship with the outside world.

There appears to be some belated recognition on the part of the Bush administration that Beijing's tactics may in fact be strengthening the hand of hardliners within the Uyghur population. In December of 2002 Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights, Labor and Democracy Lorne Craner traveled to Xinjiang and spoke there, "insisting that Washington has not 'bought into the notion that Uyghurs are terrorists' — a speech that mollified some Uyghurs who had been angered by the designation of EITM" (Kurlantzick 266-7). A decision in early November 2004 to allow cleared Uyghur detainees in the Guantanamo Bay prison center to seek refuge in third party countries rather than forcibly repatriating them to China drew strong public ire from the CCP authorities, and signaled some American sympathy for Uyghur claims ("China faults Bush on Iraq").

Dru Gladney in a September 2002 Current History article suggests that to avoid a future "West Bank scenario" in Xinjiang, the U.S. must go further. Gladney offers his own proposals for the Chinese state's adoption, modeled on experiences in Alaska (granting dividends from natural resources to the local minority); Scotland (offering some form of genuine autonomy in domestic politics while retaining control of foreign policy and trade); Hawaii (giving a real voice to the local minorities rather than shutting them out of the existing political process); and Australia (recognizing the rights of indigenous peoples to have input on the development of their land) (270). As evidently necessary and desirable as these compromise solutions may seem to the outside reader, there is scant evidence that Gladney's prescriptions are currently held in any high regard, or even considered as serious options for dealing with the Xinjiang problem, by Beijing. How much further the U.S. is interested in going in its public statements in promulgating these sorts of solutions is debatable, given Beijing's lack of enthusiasm.

The U.S., having suffered the worst form of blowback imaginable from its support of the Afghan mujahadeen against the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 80s, will most certainly limit any U.S. endorsement of Uyghur nationalist aspirations to supportive rhetoric (Fuller and Lipman 352). Even that possibility remains doubtful, given the degree to which China is increasingly seen as a dominant economic and regional power; too much pressure from the United States on the Uyghur issue risks riling a Beijing government already wary over the increased American presence in Afghanistan and Central Asia — a suspicion reinforced by recent statements on the need for a more aggressive containment of China by prominent conservative intellectuals in institutions with close ties to the administration (Fuller and Lipman 352; Goldberg). Although many Uyghurs would desperately like to play a role in curbing the rise of Chinese power, it does not seem likely to be welcomed by U.S. policymakers at this moment.

Prospects for Islamic Militancy and the Future of Xinjiang The Uyghur people of Xinjiang have no shortage of grievances with which to feed their mutually antagonistic relationship with the CCP. Discriminatory state policies, both deliberate and unconscious, limit their political and economic rights within their homeland, and a government-encouraged influx of Han immigrants to Xinjiang threatens to swallow up the Uyghurs as surely as the desert sands. Not only do the Uyghurs face demographic marginalization in the face of wave of newcomers from the east, they also face concerted efforts by the ruling state apparatus to obliterate the public practice of their traditional religion and erase their distinct identity in favor of forced cultural assimilation.

That these factors have strengthened resistance and a sense of aggrieved solidarity amongst the formerly disparate and disunited oasis Turkis is unsurprising — if anything, it may be the relative quiescence on the part of the Uyghurs thus far that is most remarkable. Whether this political balance is sustainable in the face of unrelenting Chinese pressure is the critical question for Xinjiang's future. Barring a drastic reconsideration on the part of the CCP leadership of the wisdom of its "Great Leap West" and the "Strike Hard" campaign, and assuming that democratization or decentralization of power does not come to China any time soon, Uyghur grievances will continue to be compounded as the political, material economic, and cultural threat is reinforced by successive waves of Han migrants. Uyghur nationalists have already experienced discouragement as the United States, once seen as the best hope for recognition of their claims of persecution, has sided with the Chinese government and muted its criticisms in order to ensure Beijing's acquiescence for its war on terror in Central Asia and the greater Middle East.

With the world's attention focused on the U.S. military intervention in Iraq (and now, to a declining extent, in Afghanistan), the Uyghurs continue to languish in relative obscurity at the periphery of news reports. In the face of this marginalization the Uyghur leadership may come to conclude that the only alternative left to them against Beijing's "cultural genocide" remains the kind of violent, activist resistance that the CCP already characterizes the whole movement as taking part in. Damned either way they turn, stymied in their attempts at employment or self-advancement, harassed by the state, and forcibly estranged from their historical cultural roots, young Uyghurs may see little future in continued submission. They could quite conceivably decide to jettison their current leaders in favor of the direction that a number of them are known to have already received in the training camps of Al Qaeda.

While Uyghur terrorists, with the essentially limited goal of ending Chinese occupation of Xinjiang, would be unlikely to achieve the kind of global scope that Osama bin Laden's metastasizing terror network has achieved, a potential willingness on their part to link up with other similarly-minded militant groups in neighboring Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Central Asia raises the possibility of a widening front in the war on terror on China's western frontier — something no one, be they Uyghur, Chinese, or outside observer, should desire. December 6, 2004 revision (primarily maps, format) .rtf file here Acknowledgements and Thanks - Claude Cookman, for editing assistance - Husain Haqqani, for research and editing assistance - Claudia Morgenstern, for editing assistance Works Cited ___. "China faults Bush on Iraq." Associated Press 2 Nov. 2004 (Accessed 12/01/04) ___. "China Muslims face haj restrictions." Al Jazeera 28 Oct. 2004 (Accessed 12/01/04) ___. "Resolution of the East Turkestan National Congress" East Turkestan Information Center 17 Oct. 2001 (Accessed 12/05/04) ___. "Separatist leader handed over to China." Dawn 28 May 2002 (Accessed 12/01/04) ___. "Several killed in ethnic clashes in central China: officials." Associated Press 1 Nov. 2004 (Accessed 11/18/04) ___. "Uyghur terror group smashed in raids." AFP 23 Jan 2001 (Accessed 12/01/04) Christoffersen, Gaye. "Constituting the Uyghur in U.S.—China Relations: The Geopolitics of Identity Formation in the War on Terrorism" Strategic Insight 2 Sep. 2002 (Accessed 11/30/04) Fuller, Graham E. and Jonathan Lipman. "Islam in Xinjiang" in Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland, S. Frederick Starr, ed. New York: Central Asia Caucasus Institute, 2004. Gladney, Dru. "Cyber-Separatism and Uyghur Ethnic Nationalism in China". Center for Strategic and International Studies 5 Jun 2003: (Accessed 11/13/04) ___. "Responses to Chinese Rule." in Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland, S. Frederick Starr, ed. New York: Central Asia Caucasus Institute, 2004. ___. "Xinjiang: China's Future West Bank?" Current History Sep. 2002: 267-270 Goldberg, Mark. "Did He Just Say Panda Huggers?" TAPPED: The American Prospect Online Weblog 9 Nov 2004 (Accessed 11/18/04.) Kurlantzick, Joshua. "Repression and Revolt in China's Wild West" Current History Sep. 2004: 262-267. Millward, James A. and Peter C. Perdue. "Political and Cultural History Through the Late 19th Century" in Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland, S. Frederick Starr, ed. New York: Central Asia Caucasus Institute, 2004. Millward, James A. and Nabijan Tursun. "Political History and Strategies of Control, 1884—1978" in Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland, S. Frederick Starr, ed. New York: Central Asia Caucasus Institute, 2004. Roberts, Sean R. "A 'Land of Borderlands': Implications of Xinjiang's Trans-border Interactions" in Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland, S. Frederick Starr, ed. New York: Central Asia Caucasus Institute, 2004. Rudelson, Justin J. Oasis Identities New York: Columbia University Press, 1997. Rudelson, Justin J. and William Jankowiak. "Acculturation and Resistance: Xinjiang Identities in Flux" in Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland, S. Frederick Starr, ed. New York: Central Asia Caucasus Institute, 2004. Tyler, Christian. Wild West China: The Taming of Xinjiang. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2004. Wiemer, Calla. "The Economy of Xinjiang" in Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland, S. Frederick Starr, ed. New York: Central Asia Caucasus Institute, 2004. Wright, Robin and Peter Baker. "Musharraf: Bin Laden's Location Is Unknown". Washington Post 5 Dec. 2004 (Accessed 12/05/04) Yom, Sean L. "Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang" Self Determination in Focus 2001 (Accessed 12/01/04)

Posted to:

Minorities

Pakistan

+Russia & its neighbors

Uzbekistan

+ Afghanistan

Uighurs

Islamist radicalism

MCMasterChef's Kitchen

Islam in South Asia Course

http://cheznadezhda.blogharbor.com/blog/_archives/2004/12/6/197546.html

Tengri alemlerni yaratqanda, biz uyghurlarni NURDIN apiride qilghan, Turan ziminlirigha hökümdarliq qilishqa buyrighan.Yer yüzidiki eng güzel we eng bay zimin bilen bizni tartuqlap, millitimizni hoquq we mal-dunyada riziqlandurghan.Hökümdarlirimiz uning iradisidin yüz örigechke sheherlirimiz qum astigha, seltenitimiz tarixqa kömülüp ketti.Uning yene bir pilani bar.U bizni paklawatidu,Uyghurlar yoqalmastur!

Link List-1

- Amnesty International

- Eastturkistan Goverinment In Exile

- Free Eastturkistan

- Free Ostturkistan

- Gesellschaft für bedrohte Völker

- Google News

- Gérmanche Ügününg-1

- Gérmanche Ügününg-2

- HÖR KÖK BAYRAK

- Küresh Küsen Torturasi!

- Norwegiye Uyghur Kommetiti

- Radio Free Europa

- The Amnesty in USA

- The History Of Uyghur People

- The News of BBC

- The Origin Of Uyghur

- Uyghuristan Torturaliri

- Uyghuristangha Azatliq

- Wellt Uyghur Congress

- Wetinim Uyghur Munberi

Uyghuristan

Freedom and Independence For Uyghuristan!

Link list-2

- Deutsche Welle

- Deutschen Literatur Haus

- Die Berumte Dichter in Deutschland

- Dr.Alimjan Torturasi

- Frankfurter Rundschau

- Free the Word! 2010 Festival of World Literature

- Ghayip Dunya

- Habercininyeri

- International Pen

- International Pen Uyghur Center

- Liebe Gedicht von Deutschen

- Maariponline.org

- Meripet

- My English Teacher and Uyghur Artist

- Nobelprize Org

- Peace and Liberty for Eastturkistan

- Radio Free Asia

- Religion

- The Brother State Hungary

- The Religion Of Islam

- The Rial History Uyghur People

- The Root of Modern uyghur

- Truth About China

- Türk Kerindashlar

- Türkmen Qérindashlar

- Uyghur and Uyghur Kulture

- Uyghur People Online

- Verwant Land Uzbekistan

- World Famous Gallerie

- Üzbek Qerindashlar

FREE UYGHURISTAN!

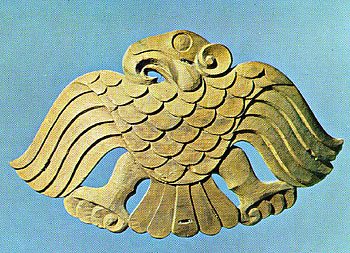

SYMBOL OF UYGHUR PEOPLE

About Me

Blog Archive

-

▼

2008

(258)

-

▼

May

(26)

- KÖKTE KÜNNUR YERDE UYGUR, QUYASH TUGHUMDUR DILIMDA...

- "Mexmut qeshqiri we u yashighan dewr" namidiki xel...

- Sherqiytürkistan Birliki Teshkilati Wekilliri Köli...

- Guantanamo: Europa soll unschuldig inhaftierten Ui...

- Amérika Hökümiti Uyghur Mehbuslarni Amérikigha Oru...

- Türklerning Mehmut Qeshqiri SöygüsiMuxbirimiz Erki...

- Der Tod als StrafeIm Jahr vor den Olympischen Spie...

- Chinas Kampf gegen die UigurenChina/ 11.04.2008Gro...

- Uyghur Separatism and the Politics of Islam in Chi...

- East Turkistan Or Uyghuristan?Hashir WahidiUntil n...

- Turpanda Yéqinda Yüz Bergen Milliy Qarshiliq Herik...

- The Uyghurs Homeland Eastturkistan The Uyghurs ar...

- China rechnet mit mehr als 50 000 Toten - Halten d...

- Uyghur People Should Get Self Determination: Group...

- Yash Yazghuchi Küresh Atahanning Maaripning Uyghur...

- Mehr als 12 000 Tote nach Beben in China Foto: ap ...

- Sherqiytürkistan Birliki Teshkilati Xelqara Paaliy...

- Xitay Sheherlirige Bérishni Ret Qilghan Rushengüln...

- Uyghur Yazghuchisi Küresh Atahanning 'Milletchilik...

- Xitayni Tinch Özgertishning Heqiqiy Küch Salmiqi ...

- Amérika Xelqara Diniy Ishlar Komitétining Doklatid...

- Xitay, Afghanistan We Pakistanda Taliban Hem El - ...

- Chinese Uighur exile urges Olympic boycott over 'g...

- Dunya Mutexessislirining Uyghur Milliy Herkitige B...

- Bérlindiki Uyghur Rehberlirini Terbiyelesh Simnari...

- Uyghur yazghuchisi Küresh Atahanning pikir- Neshri...

-

▼

May

(26)