Situating the Uyghuristan Between China and Central Asia

Ildikó Bellér-Hann, M. Cristina Cesàro, Rachel Harris and Joanne Smith Finley

Divergent Traditions of Scholarship

This edited volume explores the social and cultural hybridity or ‘in-between-ness’

of the Uyghurs, an officially recognized minority mainly inhabiting the Xinjiang

Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China, with significant

populations also living in the Central Asian states. It seeks to bridge a perceived gap

in our understanding of this group, which too often has fallen between two regional

traditions of scholarship on Central Asia and China: Central Asian studies, with its

focus on the post-Soviet Central Asian states, and Sinology.

The ‘Great Game’ in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Central

Asia was a historical period that stimulated intense political, economic, military and

scholarly interest in the region then more commonly known as Chinese (or East)

Turkestan and its oasis inhabitants, then commonly referred to as Turkis/Turks,

Muslims or Sarts. This period of global strategic interest came to an end with the

establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, and the region was for a

time largely marginalized in Western scholarship. As China began to open up to

the outside world in the 1980s, academic interest in what was now the Xinjiang

Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) flourished again. With the disintegration of

the USSR in the early 1990s, the study of Central Asia made its own comeback as

the region offered a comparatively accessible environment both for field study and

archival research. Yet communication between the two new fields has so far been

limited. Although scholars working on the post-Soviet Central Asian republics tacitly

acknowledge cultural ties and continuities between the peoples of the former Soviet

territories (Russian or West Turkestan) and the inhabitants of Xinjiang (Chinese or

East Turkestan), they seldom concern themselves with the latter. Meanwhile, those

who approach the study of Xinjiang from a sinologist’s perspective rarely extend

their research interests across China’s north-western borders.

The principal reason for the lack of cross-fertilization is evidently related to the

different linguistic backgrounds and abilities of scholars working on the respective

regions. Sinologists are primarily trained in the Chinese language (making it easier

to conduct fieldwork and access documentary data in the Chinese language), while

Central Asia scholars tend to be trained in Russian and/or the Turkic-Altaic languages.

While it is common to find scholars who combine their main expertise in Chinese or

Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia

Russian with (an often less thorough) knowledge of one or more Turkic languages

and are thus equipped to tackle one or other of the two ‘Turkestans’, it is rare to find

mastery of both Chinese and Russian in the same individual. Yet the phenomenon

must also be due in part to other, cultural factors. To many Central Asia scholars, for

example, the Uyghurs appear as an exotic extension of Central Asian Turkic-Islamic

culture, one which does not fit comfortably within the post-Soviet, post-socialist

framework of their enquiry. Another distinction between these comparatively new

fields is that scholars working from the Central Asian perspective often tend to be

interested in social and cultural practices and processes, focusing on things Uyghur,

Central Asian, Turkic or Muslim, while those starting from a sinological perspective

often have a predominantly territorial focus: Xinjiang (Chinese, lit. ‘New Border’ or

‘New Dominion’ of the Chinese polity), majority-minority configurations, Uyghur

nationalism, repression, secession.

Public Representations

When the history, culture or the contemporary political situation of this region

and this people emerge into the public sphere, their representations are equally

schizophrenic. In May 2004 the British Library in London mounted a major

exhibition, ‘The Silk Road’. Centred on the much contested discoveries of early

Buddhist artefacts, frescos and manuscripts made by Sir Aurel Stein in the regions

of Khotän and Dunhuang, the exhibition included many loans from the Chinese

government, among them a recreation of a Dunhuang cave complete with Buddhist

frescos. The term ‘Uighur’ [Uyghur] appeared only fleetingly, in reference to a

Tibetan document written in the Old Uyghur script, while there was just one brief

reference to the last millennia of Islamic culture in the region. Instead, a section of the

exhibition entitled ‘Play on the Silk Road’ featured a ‘Letter of Apology for Getting

Drunk’ from the kingdom of Gaochang, written in Chinese characters. The notes

explained: ‘By the eighth century there was a Chinese wine making industry using

mare’s teats grapes from Gaochang’. Contrast this with another major and extremely

well attended exhibition, ‘The Turks’, held in the Royal Academy in London in the

following year. This exhibition included many loans from the Turkish government.

Here the Uyghurs featured more prominently as an early stop-over on the march

of Old Turkic, and subsequently Islamic, art which advanced via the Seljuks and

Timurid Samarkand towards the glories of Ottoman Turkey. The exhibition included

a ninth century fresco from the capital of the Uyghur kingdom of Khocho. It would

have taken an observant visitor to both exhibitions to realize that Gaochang is in

fact the Chinese name for Khocho, and that the kingdom in question was one and

the same. This is not to accuse either exhibition of deliberate misrepresentation,

http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/features/silkroad/main.html (accessed 23 August 2005).

http://www.turks.org.uk/ (accessed 23 August 2005).

In fact, and one must have some sympathy with the author of the entry, the name

‘Kucha’ (another city along the Silk Road further to the west, Qiuci in Chinese sources and

Kösän in modern Uyghur) is given mistakenly on the ‘Turks’ website for Khocho (also

sometimes written Kocho but never Kucha).

Introduction

merely to note the strikingly different representations that can arise from differing

perspectives, agendas and traditions of scholarship. The challenge lies in developing

a vision of Uyghur history, society and culture which can encompass these multiple

perspectives.

The ‘Uyghur Problem’

The Uyghurs’ in-between-ness arguably underpins the key problems which they,

as a group, face today. The year 2004 brought a flurry of studies on the ‘Uyghur

problem’, viewed from political and strategic perspectives, as the Central Asian

region once again came to prominence in the global political arena (Dillon, 2004;

Gladney, 2004; Millward, 2004). These studies focus on Uyghur separatism and

unrest, and the rise of radical Islam; on China’s ongoing ‘Strike Hard’ anti-separatist

campaign; and on its manipulation of the ‘global war on terror’ as it colours Uyghur

opposition to Chinese rule ‘Islamic terrorism’. An edited volume on ‘Xinjiang’

(although it largely focuses on the Uyghurs) published in the same year, probes

some of the historical, demographic, socio-economic and political issues in greater

depth (Starr, 2004). Situating Xinjiang as China’s ‘borderlands’, its authors argue

that the Chinese state’s penetration or ‘domestication’ of the region has accelerated

during the 1990s, and with increasing rapidity into the twenty-first century (see also

Becquelin, 2004). This ‘domestication’ of Xinjiang entails state attempts to establish

continuities in demography, communications, and language, primarily through

strategies of construction and development under the Western Development Policy

(Xibu da kaifa), but also through the media and more coercive policies of control

such as population transfer and education. The development of infrastructure,

notably the extension of the railway to Qäshqär [Kashgar] bringing greater numbers

of Chinese migrants into the Uyghur heartlands, and the growing insistence on the

use of Chinese language as the medium of instruction, are the prime examples of this

tendency (Dwyer, 2005). The stepping up of religious repression which in Xinjiang

is especially targeting Islamic practices is a further example of coercive tendencies.

These policies may be interpreted as leading inevitably to the acculturation of the

Uyghurs, yet they are also contributing to the strengthening of Uyghur nationalist

sentiment in reaction to perceived Han discrimination and increased Han competition

for education, employment and resources.

Looking across the border, it was argued in the early 1990s that the newly

independent Central Asian states would have a strong impact on political

developments for the Uyghurs. These states, it was thought, would serve as models

of independent governance, market capitalism and democracy, and also as new sites

for Uyghur political organizations, which were expected to offer support to their

‘ethnic brothers’. By 1996, scholars, international observers and analysts had begun

to realize that these hopes were largely illusory, and were judging the states as failed

models in their politics, economies and nationality policies. This notwithstanding,

young Uyghurs in Xinjiang continued to be inspired toward their own secession

movement at least until, and in some cases beyond, the Ghulja riots of February

1997. By the start of the new millennium, it was abundantly clear to both local and

Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia

international observers that, far from providing safe havens for Uyghur nationalists,

the Central Asian states were increasingly complying with Chinese demands to

crack down on Uyghur separatism, levied through the mechanism of the Shanghai

Cooperation Organization (see Dillon, 2004).

Problems with Names

As we suggested above with reference to the London exhibitions, the complex

problems inherent in trying to ‘situate the Uyghurs’ are highlighted by the lack

of agreement over names. The political arguments over the links between the

contemporary Uyghur ethnic group and the pre-Islamic Old Uyghur kingdoms

are well rehearsed, but the dual perspective remains constant. Chinese official

histories place Uyghur roots in what is commonly termed the ‘Western Regions’

(Ch. xiyu), a term which clearly makes sense only when viewed from China.

Uyghur nationalist histories, on the other hand, reject the Chinese perspective on

their homeland. Turghun Almas, in his influential history The Uyghurs, writes: ‘One

must state definitively: the motherland of the Uyghurs is Central Asia’, a region

which he describes as an ‘ancient golden cradle of world culture’ (see Bovingdon,

2004: 357−63). Meanwhile, Central Asians (both Soviet and post-Soviet) term the

region ‘East Turkestan’ (viewed from the perspective of nineteenth-century Russian

or West Turkestan), and Uyghur separatists remain divided in their preferences

between the pan-Turkic ‘East Turkestan’ and the less inclusive ‘Uyghuristan’. Both

these names are of course banned in China, where Chinese histories of the East

Turkestan Republic (1944−49) refer rather to the ‘Three Districts Revolution’ [Ch.

Sanqu geming, U. Üch wilayät inqilawi].

These various binary oppositions expressed in the form of place names can be

easily understood if we consider Xinjiang’s position in terms of its present political

subordination to China. Yet they mask far more complex historical processes.

Toponyms are always politically loaded, and may at different times in history (and

from the perspectives of different actors) be expressions of local identity, emblems

of enforced state control, or indeed a locus of contested political power. Thus,

although the generic name ‘Xinjiang’ is today used as a short-hand designation

for the region by political power holders, most of its inhabitants and outsiders,

including the international scholarly community, it continues to be contested by

Uyghur separatists and émigré groups pursuing a nationalist agenda. As a blanket

term, the name ‘Xinjiang’, even in its full incarnation (Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous

Region), fails to do justice to the region’s rich ethnic and cultural diversity, though

the same could equally be said of the names of many of today’s large nation-states.

A brief glimpse at the history of toponyms in Xinjiang quickly dispels the notion

either that territorial continuity presumed cultural continuity with China, or that this

vast region itself enjoyed cultural and political homogeneity. As is well documented,

This term could be used to cover all the regions to the west of China, from the Middle

East to South Asia, but was also used in a more specific sense to refer to the Tarim basin

area.

Shinjang, the loan from Chinese, is regularly used in spoken and written Uyghur.

Introduction

the name ‘Xinjiang’ (New Dominion) was imposed by the Manchus during the

Qing period, and reflected the imperial perspective. By contrast, the designation of

‘East Turkestan’ represented the Russian view, which emphasized continuities with

the other Turkic-speaking regions of Central Asia (West Turkestan). This Russian

distinction between East and West Turkestan incorporated both the linguistic and

cultural continuities connecting the two regions and the political/colonial boundaries

separating them.

Yet even as cultural continuities drew together this vast terrain, it was characterized

also by a sense of political disintegration. The names used for the oases of East

Turkestan prior to Manchu occupation suggest a lack of unifying political structure,

and this condition was reflected for some time in locally used terminology even

following the region’s formal incorporation into the Qing Empire in 1884. Indigenous

sources dating from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries used the loose

designation of ‘Six Cities’ (Altä Shähär) to refer to the oasis settlements south of

the Tianshan (Heavenly Mountains), a term which simultaneously reflected a loose

sense of shared features as well as the fragmented nature of the region as a whole.

Fluctuations in local usage concerning the exact identity of the Six Cities suggest that

the term denoted a rather general territory, and expressed the relative autonomy of the

cities, the fluid nature of the connections between them, and their respective lack of

fixed political rank. Xinjiang’s toponyms also reflect changing religious beliefs over

time. A late nineteenth century indigenous source gives epithets for the Six Cities,

all projecting images of sacred places and the shrines of saints, simultaneously local

and connected to the Islamic umma and the Middle East (Katanov, 1936: 1220−21).

That these epithets were of Arabic and Persian derivation suggests that the naming

process embodied an implicit claim to exclusively Islamic religious traditions, as

well as a desire to disclaim the pre-Islamic past to which the Old Uyghur Kingdoms

belonged.

In this way, Xinjiang toponyms encapsulate both the contested, political nature

of the symbolic appropriation of space and the multiplicity of cultural influences that

have come to bear on the region throughout its troubled history. Political contestation

over the region and, by extension, over its indigenous population, continues to play

out today with Chinese names used in the public domain to denote places which

Uyghurs and most other minorities refer to using traditional Turki designations

(Qumul – Hami; Ghulja – Yining, and so on). These simple binary approaches are

implicitly fostered by Chinese state discourse and explicitly reproduced by Uyghur

actors situating themselves in terms of cultural difference from, and political

opposition to, the Han. They may serve us well when positioning the (modern)

Uyghurs as political − and politicized − beings. Yet they are deficient if our aim is to

create a rounded picture of the Uyghurs as social and cultural actors, and one which

Qäshqär is listed as Azizanä or the City of the Saints; Yäkän [Yarkand] as Piranä, the

City of Patron Saints; Khotän as Shähidanä, the City of the Martyrs (after the great number of

martyrs buried there); Aqsu as Ghaziyanä, the City of the Ghazis (the Triumphant ones, after

the Muslim fighters who victoriously fought for Islam), Kucha as Güli-ullanä, or the City of

God’s Governors (after the Muslim governors buried there); and Turpan as Gharibanä, the

City of Strangers (after the many pilgrims to the numerous saintly shrines).

Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia

allows for continuity and change over time and space. In this latter endeavour, a

broader, multi-faceted approach becomes necessary.

Dialogue across Borders

The majority of recent studies, then, have adopted the binary focus on Uyghur-Han

political and cultural conflict, as suggested by the contemporary political situation in

Xinjiang. They have rarely looked beyond the construction of Otherness of, and by,

the Uyghurs in relation to the Han to consider the role of Central Asian culture (or

indeed other cultures) in the shaping of Uyghur identity. With this volume we aim to

fill this gap, approaching the Uyghurs with a focus on the dynamics of historical and

contemporary contacts between China and Central Asia. We consider these contacts

as they have been maintained through, for example, intermarriage, education,

migration and trade; through shared institutions (Islamic, Turkic, political and sociocultural)

and during different historical periods (pre-colonial, colonial, socialist, and

‘socialist market economy’). We hope that this perspective will afford fresh insights

into the complexities of Uyghur social and cultural institutions over time, and open

up new avenues for future studies of the region and its peoples.

This edited volume, like the international conference from which it arises, was

conceived with the aim of promoting dialogue across national, disciplinary and

linguistic borders, bringing together Xinjiang specialists who have hitherto worked

in relative isolation, and narrowing the chasm between Sinologist and Central

Asianist perspectives. It is hoped that the project will pave the way towards a new

style of integrative research, leading to further collaborations among scholars from

different disciplinary backgrounds and with different linguistic strengths to bring

the Uyghurs to a more prominent position within Asian scholarship. The conference

‘Situating the Uyghurs between China and Central Asia’ was held at London’s

School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in November 2004. Invited speakers

were asked to respond to the following questions:

To what extent can Xinjiang’s Turkic-speaking Uyghur Muslim population be

described – or describe itself – as part of China and/or part of Central Asia?

Beginning with the Qing administration, which first encouraged mass Han

immigration to the region in 1821 and had by 1884 made Xinjiang an official

province of China, how far has successive Chinese rule − imperial, republican,

socialist − succeeded in disembedding the Uyghurs from the Central Asian

cultural context and integrating them into China?

As a result of almost 200 years of contextual change, have the Uyghurs now

developed characteristics that render them ‘culturally autonomous’ from both

Central Asia and the People’s Republic?

To what extent may Uyghurs be described as ‘culturally hybrid’? Or do they

rather negotiate dual and multiple identities that shift and change according to

social and political contexts?

•

•

•

•

Introduction

The twelve scholars whose revised and edited chapters appear in this volume

address these questions from a range of disciplinary perspectives including history,

anthropology, sociology, literary studies and musicology. All the contributors have

an intimate knowledge of the region based on long-term stay, library and archival

research, while several Uyghur contributors offer rare insiders’ views. The volume’s

emphasis on micro-level, fieldwork-based approaches provides a wealth of original

and detailed material which, due to the constraints typically placed on scholars

working in this region, previous publications have often failed to deliver. Methods

such as case study permit an understanding of current identities (social, cultural,

religious) as they are experienced by the actors themselves (Roberts, Smith Finley,

Waite). The micro-approach is complemented in other chapters by a focus on the

complicated interplay of larger cultural currents, which may remain hidden from

local actors but which concern issues that are meaningful to them. Popular literature

(Friederich), ‘national’ and local musical traditions (Light, Harris), food practices

(Cesàro), and life cycle rituals (Bellér-Hann) are all important constituents of

modern Uyghur identity, which despite evolving through multiple cultural influences

may nonetheless become articulated as ‘our traditions’. While in some chapters the

Central Asian component of Uyghur identity remains comparatively implicit, those

chapters that explicitly address the tripartite structure suggested by the conference/

volume title often end up challenging this neat classification. In one way or another,

each chapter implicitly addresses the larger issue of the tension between that

dimension of social reality experienced by actors and that which remains hidden

and lies beyond their control and agency. The historians have concentrated on

larger currents invisible to actors, cautioning that representations of the Uyghurs

must always be considered within the specific historical context in which they were

produced (Kamalov, Newby). On the other hand, two of the Uyghur authors present

cases in which the Uyghurs explicitly emerge as active shapers of their own destiny:

the ongoing debate surrounding name and surname reform (Sulayman) and local

responses to the promotion of Muslim shrines as tourist sites (Dawut). Here, the

background of the authors is significant, as the Uyghurs are presented as agents

rather than helpless victims of the current political situation.

Some of the authors in this volume have chosen to adopt a comparative framework

in order to tease out the links and correspondences (or lack of them) between Uyghur

and Central Asian/Chinese cultures, but each voices caution about the comparative

endeavour. As Ildikó Bellér-Hann argues in her chapter, highlighting the centrality of

the veneration of the dead among the Uyghurs may inadvertently supply apologists

of Chinese political and cultural hegemony over Xinjiang with new material. On

the other side of the border in the independent Central Asian republics, pointing out

commonalities among the Turkic groups may serve as a good antidote to former

Soviet nationality policies (which, through emphasizing real or imagined differences,

were largely responsible for the emergence of modern Central Asian ethnic groups),

but it may also serve pan-Turkic ideologies. The chapters gathered in this volume

have no such agendas. None of the authors embraces extreme cultural relativism

or universalism. They do try to go beyond the simple binary oppositions (Han v

Uyghur) and comparisons (assumed affinities between Uyghurs and Central Asians)

to substantiate or refute assumptions and claims of similarity and difference.

Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia

The editors have made no attempt to impose a single unified viewpoint on the

authors. The result is that while several chapters stress cultural continuities with

Central Asian peoples, practices and experiences over time, attention is also given to

differences (real or perceived) between the Uyghurs of Xinjiang and other Central

Asian groups, and to examples of accommodation, adaptation and compromise

between Uyghurs and Han Chinese. Indeed, one of the most interesting aspects of

the conference ‘Situating the Uyghurs’ was the striking contrast between speakers

in their attitudes and assumptions, depending on their scholarly background and/or

sphere of enquiry. The conference, which was well attended by Uyghur students and

residents in the UK, also brought home to us the sensitivities of discussing aspects

of Han acculturation with a Uyghur audience. In a field where politics is all but

inescapable, it is hard to state as matters of simple fact that, for example, Uyghurs

have absorbed many foodways from the Chinese, but are very little influenced

by Chinese music. Is it possible that a search for the meanings behind this might

conclude innocently that Chinese music is indigestible and Central Asian cuisine

dull? This volume arises out of, and continues, that ongoing dialogue.

The Chapters

Drawing on a combination of fieldwork in Uyghur communities in Xinjiang and

historical research into the nature of ‘tradition’ in the pre-socialist era, Bellér-Hann

attempts to substantiate the hitherto tacit assumption of cultural links between the

Uyghur and other Turkic-speaking Central Asian groups through looking at life

cycle rituals in their historical contexts. Her enquiry also draws on ethnographic

parallels from Han Chinese culture, and suggests that levels of difference must be

distinguished if we are to allow for human diversity without losing sight of broad

underlying commonalities and examples of accommodation and cultural borrowing.

She argues against the constraints imposed by binary oppositions, and calls for

the inclusion of other groups (such as the Hui) into the enquiry, who may hold the

key to understanding the complicated interplay between Han and Uyghur cultural

practices.

The Kazakhstan-based Uyghur historian, Ablet Kamalov, contributes a strongly

argued and thoroughly sourced contention that modern Uyghur national identity was

initiated in and largely shaped by Russian Central Asia. Both this and the British

historian Laura Newby’s chapter serve as important counter-balances to the oft-cited

contention that Uyghur national identity is largely created by, or in response to, the

Chinese state (Gladney, 1990). Based on detailed reading of Qing sources, Newby

asserts that a sense of community and discrete identity was shared by the peoples

of the Altä Shähär (Six Cities, contemporary southern Xinjiang) as early as the

eighteenth century, and that this was promoted by inter-oasis trade and marriage, and

Qing policies including population transfer. While she acknowledges the commonly

accepted view that the ethnonym ‘Uyghur’ fell into disuse following the fall of the

Uyghur Khocho kingdom and re-emerged only in the twentieth century, she argues

that the absence of an ethnonym does not preclude a shared sense of identity.

Introduction

The flipside of the commonplace assumption of the recent nature of Uyghur

national identity is the notion of powerful local or ‘oasis’ identities, Qäshqärliq,

Turpanliq, etc. (Rudelson, 1997). These local or vernacular identities within

contemporary Uyghur culture are emphasized in only one of the chapters, in the

context of musical traditions. Rachel Harris takes a detailed look at the music of

the Twelve Muqam to debunk the various hotly contended myths about their

origins. Arguing that they are neither ‘Arab music’ nor ‘of the Western Regions’

(Xiyu), she instead situates the various local Uyghur Muqam traditions (Qäshqär-

Yäkän, Turpan, Dolan, etc.) within a mosaic of distinct yet inter-related local

musical traditions practised by peoples across the Central Asian region. Harris also

expresses ambivalence about the comparative project, warning that comparison of

de-contextualized cultural products (a popular activity with early twentieth century

comparative musicologists) is fruitless if their performance contexts and meanings

are not taken into account.

As discussions arising from the conference demonstrated, the Uyghurs’ ‘inbetween-

ness’ soon escapes the neat China-Central Asia dichotomy. In his recent

edited volume, Frederick Starr discusses the ‘external gravitational fields’ which

exert force on the region of Xinjiang, commenting that ‘it is hard to find another

region on which such diverse cultural forces have been so consistently exerted’

(Starr, 2004: 7). From the penetration of Buddhism from India to the advent of Islam

from the Arab-Persian world; from the waves of early nomadic invaders and settlers

who entered the region from Siberia, to periods of Chinese dynastic rule under the

Han and Tang; from nineteenth century Russian models of modernity and reform to

the global information networks and cultural flows through which Uyghurs today are

circumventing their oft-cited position in China’s backyard, clearly any consideration

of Uyghur ‘in-between-ness’ must take into account multiple spheres of influence

and interaction.

Several of the chapters consider the impact and reception of globalized currents

in Uyghur culture and society. Michael Friederich considers a range of cultural

influences on the work of contemporary Uyghur poets. His chapter alerts us to

the possibility of multiple and shifting interpretations of ‘east’ and ‘west’, as he

argues that the Uyghurs’ historical westward orientation (first towards the Islamic

world, then the Russian sphere) has been replaced under the PRC by a circuitous

flow of literary stylistic influence emanating from Europe and arriving in Xinjiang

via Beijing. The most controversial example of global flows entering the Uyghur

sphere is, of course, the penetration of new forms of Islam ranging from reformism

to militancy. Edmund Waite brings a rare fieldwork-based perspective to bear on

this much debated subject. In his discussion of the changing nature and sources

of religious authority in contemporary Qäshqär, he argues that varying degrees of

religious repression and secularization practised under PRC rule formerly served

to isolate the religious community and promote the local authority of the mosque

community. Following the opening of Xinjiang’s borders in 1987, however, this

local authority has been increasingly challenged by reformist ideologies which

emanate from Saudi Arabia and arrive in Qäshqär via Central Asia. Working on the

other side of the border with a Uyghur community in Almaty in Kazakhstan, Sean

Roberts also discusses changing understandings of Islam. He explores the complex

10 Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia

question of the interaction of faith with ethnic national consciousness, and argues

that local identity is shaped by a multiplicity of cultural influences emanating from

Islam, China, and the Soviet and post-socialist experience.

The contradictions inherent in these competing strands of influence on Uyghur

culture also underlie contemporary issues of development. One important aspect

of China’s domestication of Xinjiang is the fast-growing industry of Han Chinese

tourism in the region. Rahilä Dawut’s chapter, based on a wide-ranging field

survey, discusses the problems arising from attempts to re-brand Islamic shrines

as tourist attractions. Dawut considers local reactions to the contradictory trends

of the pull of tradition and the promotion of tourism, showing local people to be

creative actors rather than pawns in a political game. She argues that the Xinjiang

authorities’ mistrust of shrine pilgrimage, which they equate with Islamic militancy,

is fundamentally misplaced and arises out of official misconceptions of the different

strands of Islam in the region; in fact the militants fiercely oppose shrine pilgrimage.

Her chapter also highlights the lack of continuity between policies in inner China

and in Xinjiang, contrasting the liberal policy on Han Chinese temple fairs with the

ongoing official mistrust of Uyghur shrine festivals.

Äsäd Sulayman’s chapter offers a valuable inside view on emerging local debates

concerning the need to reform Uyghur name and surname practices. Though the

ongoing debate may appear to be a purely linguistic discussion, it in fact encapsulates

many of the dilemmas of the Uyghurs caught amid contrastive political and sociocultural

systems. Stemming from the need to address the practical problems of fitting

Uyghur names written in the Arabic script into a national bureaucratic system based

on names composed of two or three Chinese characters, the local debate on surname

reform has developed to encompass the notion of ‘civilized-ness’ (Ch. wenming; U.

mädiniyätlik), so prevalent in Chinese public discourse. Yet intellectuals recently put

forward a recommendation that seems to highlight the contested nature of notions

of civilization: their proposition that Uyghurs should adopt a system of fixed,

hereditary patronymics such as those used by English-speaking nations implies that

name practices are just one more cultural space in Xinjiang that has been politically

coloured. A prominent Uyghur musician, when outlining some similarities between

Uyghur melodies on the one hand and Turkish and Japanese melodies on the other,

once observed pointedly to one of the editors (Smith Finley): ‘Some peoples’

cultures resemble one another more closely than others’. In the same way, urban,

secular Uyghurs have tended to desire to align themselves with the West rather than

with China.

Sulayman’s chapter is important in emphasizing that the project to ‘situate

the Uyghurs’ is in no way confined to the efforts of the authors in this volume.

Similarly, this volume does not presume to impose on a passive people an outsider

view of their situation. Uyghur intellectuals, cultural leaders and decision makers

are engaged in various ways in ongoing attempts to situate and re-situate Uyghur

culture even within the restrictive framework of the Chinese polity, and their

efforts are discussed and debated in the wider community. Other chapters in this

volume consider the issues surrounding some of these efforts from an outsider’s

perspective. Nathan Light traces the changing metaphors that Uyghur writers, artists

and musicians use in their discourses to define the group and its practices. Focusing

Introduction 11

especially on the canonization of the Twelve Muqam, he contrasts official attempts

to shape the meanings attached to this musical repertoire with individual responses

to, and subversions of, these official tropes. Light’s prime concern is to highlight

the contradictions and negotiations which underlie the surface of ethnic identity

construction.

Two chapters respond specifically to issues surrounding Chinese acculturation

of the Uyghurs, reminding us that the Uyghurs are not simply passive victims of

policies of domestication, but agents who negotiate multiple and hybrid identities in

reaction to Chinese state policies. Cristina Cesàro’s starting point is the emic view

which considers food culture to be one of the most obvious distinguishing features

of Uyghur identity. She goes on to discuss Han Chinese influences on the Uyghur

diet, and the negotiations surrounding what is today considered distinctive ‘Uyghur’

cuisine. It is indicative of the paths of Uyghur nationalism as well as the paths of

Chinese influence that Chinese food terms are now more current in the distant,

southern oasis of Qäshqär than in the regional capital Ürümchi, which has a majority

Han population. Just as cultural borrowings tend to originate in the area of greatest

contact between Hans and Uyghurs and trickle down to the rest of the region, so too

the reactive nationalist impulse to absorb and recast these borrowings as ‘authentic’

Uyghur cultural capital occurs first where exposure is most acute.

These reactive counter-trends to Han Chinese influence are highlighted in Joanne

Smith Finley’s analysis of the special position of the minkaohan (Ch. Uyghurs

educated in the Chinese language). The minkaohan (sometimes known as ‘Xinjiang’s

fourteenth nationality’) are considered by most actors − minkaohan themselves, other

Uyghurs, Han Chinese − to be neither wholly Uyghur nor wholly Chinese. Smith

Finley’s detailed case study of the life experiences of one woman illustrates the

conflicts of loyalty and internalized oppression of the minkaohan experience. This

group is both the best situated to take advantage of China’s development policy, and

at the same time arguably the group that suffers most from the Uyghurs’ in-betweenness.

Räwia (the subject of Smith Finley’s case study) actually strengthened her

sense of ethnic affiliation over the course of the 1990s in response to her perception

of Han discrimination, turning back to the Uyghur language and to Islam via the

education and upbringing of her daughter. Over the same period, she secured a

position where she could deploy her dual identity to maximum effect within the

frame of the Chinese state. In her final analysis, Smith Finley is upbeat about the

future of the urban youth: ‘The pride she [Räwia] displayed when speaking of her

minkaomin (Uyghur-language educated) daughter’s perfect command of both Uyghur

and Chinese suggested that she had begun to envisage a middle way for the new

generation: the potential for them to be simultaneously 100 per cent Uyghur (in the

sense of being Central Asian) and 100 per cent Han (in the sense of being Chinese)’.

Such an endeavour is certainly not easy, and will require strongly supportive state

policies for individuals if it is to be achieved, but this may be the best hope that the

Uyghurs can at present envisage.

12 Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia

References

Becquelin, N. (2004), ‘Staged Development in Xinjiang’, China Quarterly, 178,

358−78. [DOI: 10.1017/S0305741004000219]

Bovingdon, G., with contributions by N. Tursun (2004), ‘Contested Histories’, in

Starr (ed.) Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland (New York and London: M.E.

Sharpe), 353−74.

Dillon, M. (2004), ‘Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Far Northwest’, Durham East Asia

Series (London and New York: Routledge Curzon).

Dwyer, A.M. (2005), The Xinjiang Conflict: Uyghur Identity, Language Policy and

Political Discourse, Policy Studies 15 (Washington: East-West Center).

Gladney, D.C. (1990), ‘The Ethnogenesis of the Uighur’, Central Asian Survey,

9(1), 1−28.

—— (2004), Dislocating China: Muslims, Minorities and other Sub-altern Subjects

(Chicago, Illinois and London: University of Chicago Press).

Katanov, N.T. (1976, 1936), Volkskundliche Texte aus Ost-Türkistan, I.-II, Aus

dem Nachlass von N. Th. Katanov. Herausgegeben von Karl Heinrich Menges.

[Folkloristic Texts from East Turkestan] (Leipzig: Zentralantiquariat der

Deutschen Demokratischen Republik).

Millward, J. (2004), Violent Separatism in Xinjiang: A Critical Assessment, Policy

Studies 6 (Washington DC: East-West Center).

Rudelson, J.J. (1997), Oasis Identities: Uyghur Nationalism along China’s Silk Road

(New York: Columbia University Press).

Starr, S.F. (ed.) (2004), Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland (New York and

London: M.E. Sharpe).

http://www.ashgate.com/pdf/SamplePages/Situating_the_Uyghurs_Between_China_and_Central_Asia_Intro.pdf

Tengri alemlerni yaratqanda, biz uyghurlarni NURDIN apiride qilghan, Turan ziminlirigha hökümdarliq qilishqa buyrighan.Yer yüzidiki eng güzel we eng bay zimin bilen bizni tartuqlap, millitimizni hoquq we mal-dunyada riziqlandurghan.Hökümdarlirimiz uning iradisidin yüz örigechke sheherlirimiz qum astigha, seltenitimiz tarixqa kömülüp ketti.Uning yene bir pilani bar.U bizni paklawatidu,Uyghurlar yoqalmastur!

Link List-1

- Amnesty International

- Eastturkistan Goverinment In Exile

- Free Eastturkistan

- Free Ostturkistan

- Gesellschaft für bedrohte Völker

- Google News

- Gérmanche Ügününg-1

- Gérmanche Ügününg-2

- HÖR KÖK BAYRAK

- Küresh Küsen Torturasi!

- Norwegiye Uyghur Kommetiti

- Radio Free Europa

- The Amnesty in USA

- The History Of Uyghur People

- The News of BBC

- The Origin Of Uyghur

- Uyghuristan Torturaliri

- Uyghuristangha Azatliq

- Wellt Uyghur Congress

- Wetinim Uyghur Munberi

Uyghuristan

Freedom and Independence For Uyghuristan!

Link list-2

- Deutsche Welle

- Deutschen Literatur Haus

- Die Berumte Dichter in Deutschland

- Dr.Alimjan Torturasi

- Frankfurter Rundschau

- Free the Word! 2010 Festival of World Literature

- Ghayip Dunya

- Habercininyeri

- International Pen

- International Pen Uyghur Center

- Liebe Gedicht von Deutschen

- Maariponline.org

- Meripet

- My English Teacher and Uyghur Artist

- Nobelprize Org

- Peace and Liberty for Eastturkistan

- Radio Free Asia

- Religion

- The Brother State Hungary

- The Religion Of Islam

- The Rial History Uyghur People

- The Root of Modern uyghur

- Truth About China

- Türk Kerindashlar

- Türkmen Qérindashlar

- Uyghur and Uyghur Kulture

- Uyghur People Online

- Verwant Land Uzbekistan

- World Famous Gallerie

- Üzbek Qerindashlar

FREE UYGHURISTAN!

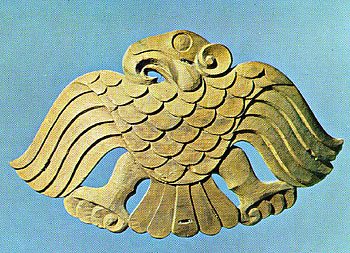

SYMBOL OF UYGHUR PEOPLE

About Me

Blog Archive

-

▼

2011

(46)

-

▼

July

(7)

- Situating the Uyghuristan Between China and Centra...

- Separatism And The War On "Terror" In Uyghuristan/...

- The Uyghurs, China and central Asia Henryk Szadz...

- Symbol Of Hope In Hotan Yet To Reap Rewards Fin...

- Clash in China’s Uyghuristan (Xinjiang) killed 20:...

- Sherqitürkistan Sürgündiki Hökümiti Gérmaniyede Pa...

- Sherqitürkistan Sürgündiki Hökümitining Sherqitürk...

-

▼

July

(7)